An unspoken assumption that often plays out in multi-generational families is that it’s the adult daughter without children who’ll be the one to take on a family caregiving role if needed. I mean, she’s the one with the abundant spare time, huge reserves of cash and the emotional bandwidth to take it on… And if she’s unpartnered, even more so.

Forget that someone ageing without children doesn’t have the unconscious safety net of children to possibly do the same for her one day, or that unless she’s financially very secure, she’s the last person who should be taking an average of a £12,000 ($15,000) hit to her annual earnings and potential savings for her old age, or that she may already have a full life and perhaps health conditions of her own to manage.

Nope. A woman without kids, despite decades of being told that she ‘wouldn’t understand’ anything about parenting should she dare to comment, is suddenly deemed to be a natural shoo-in for the demanding, unpaid role of being a parental carer. You never know, maybe it’s even a chance for her to ‘make up’ to her parents for the failure to provide [more] grandchildren?

What’s pronatalism got to do with this?

The way that all of this is deemed so ‘natural’ that to suggest it might not be either fair, workable or affordable can come as a shock to those proposing it, and may further confirm their unconscious pronatalist beliefs that there’s ‘something wrong with her’, or provoke straight-out accusations of ‘selfishness’. And this is entirely without considering that taking on those caring duties might be something she would be willing to do as a loving daughter with a sufficiently close relationship to her parent(s); it’s just the way it’s presumed and often expected to be undertaken without the support of her siblings (if there are any), even if their children have long left home!

You see, pronatalism1, the ideology that underpins the idea that the only ‘right’ way to be a fully mature woman is to be a mother, also elevates the work of mothering to a quasi-saintly status (which, by the time you discover isn’t the case, it’s too late2). At best, a pronatalist society tolerates women without children, whilst secretly (or not so secretly) either pitying or envying them. And whatever their achievements and contributions to family, community, society and civilization (which can be significant)3 they’re still seen as ‘less than’ as women because they don’t have children.

To not be a mother in our pronatalist culture is to have what sociologist Erving Goffman termed a ‘spoiled identity’,4 and you’ve only got to see the evil of Disney’s non-mother characters such as Snow White’s stepmother or Cruella de Vil, or notice how contemporary movies portray thwarted mothers in, for example, ‘The Hand that Rocks the Cradle’, ‘Fatal Attraction’ or, more recently, the awkward and divisive headmistress in the achingly hip TV series ‘Sex Education’, to see that to be a woman without children is to be cast as a deviant woman.5

So, perhaps we can see how ‘giving’ the daughter without children the chance to step into a caring role might be seen both as a compliment (part of the 'you would have been a wonderful mother’ back-hander) as well as a chance for her to redeem her spoiled identity as a ‘failed’ daughter. Why on earth wouldn’t she want that? Or expect it to be a shared, supported or financially compensated role?

Who’s going to take care of me when I’m old?

One of the reasons those of us without children are perhaps more aware of our potential care needs for our later life is that we cannot rely (unconsciously) on our children to be there for us.6 Adults without children are 25% more likely to go into a long-term care facility at a younger age and a lower level of dependency than someone with children.7 Often this boggles people’s minds but the reasons are often quite mundane - it’s can be as simple as a lack of informal, non-nursing support with the tasks of daily living that can add up and make independent living too difficult.

I was struck by this vulnerable and generous piece by Janice Walton, ‘I Am An Elderly Parent’, in which she lists some of the things her children do for her now that she is widowed and living alone at 85. They range from driving her to appointments, helping her with her computer and asking for help in solving problems - and she writes of how hard it is to both need this support and to ask for it. These are types of ‘daily living’ tasks that my husband and I offer to his mother (in her 90s) with whom we share a home, plus shopping, cooking, cleaning and many other aspects of life admin. This is the kind of ‘informal care’ that children often undertake for elderly parents and which those without children find difficult to replicate. Yes, friends can help, up to a point, but as they are likely to be in the same age bracket, they may need support at around the same time too. And with smaller families, often spread much further apart than before, there are fewer (or no) nephews and nieces around who might be able to help occasionally.

Up until now, I haven’t mentioned those who are the recipients of this care, and that’s not an accident. The needs and wishes of those needing support are often the last to be considered, which can be due to a nasty mixture of ‘compassionate ageism’8 as well as the pronatalism that elevates the childed daughter/son to the de facto head of the family (over those without children too).

The tightrope generation

Kirsty Woodard who, along with myself, Dr Robin Hadley and Dr Mervyn Eastman founded AWOC in 2014 (now the UK charity Ageing Well Without Children) called those of us ageing without children ‘the tightrope generation.’ This distinguishes us from the more commonly known ‘sandwich generation’ because, unlike those parents who are often caring for elderly parents and children still at home (whilst probably also in employment), we ‘tightropes’ are often caring for elderly parents (or others) whilst in employment, but without any safety net below us for our later years - either children or realistic hope of any state-sponsored options should we need them; the decline of such has accelerated across the developed world under neoliberalist governments, something which the Covid19 pandemic exposed.

In the UK, and as reported by Victoria on her excellent Care Mentor Substack, such cuts mean that even if you are in a financial position to afford to hire carers, there are simply not enough carers available to hire. (This is one of the reasons that my mother had to go into residential care for her dementia; my stepfather simply couldn’t find consistent carers to support her at home). Victoria also quotes Helen Walker, the chief executive of Carers UK who responded to the 2023 Autumn Budget Statement by pointing out that the government consistently fails ‘to acknowledge the devastating impact the lack of funding for health and social care services is having on millions of unpaid carers supporting older and disabled family members.’ So, if you don’t have those ‘unpaid carers’ to potentially step in, who takes care of you then?

According to 2020 data from the UK’s Office for National Statistics, by 2045 there will be a threefold increase in the number of women who reach the age of 80 without children; born in 1964, I will be one of them, as will approximately 20% of my British peers.

Yet whenever this issue is raised at a policy level, it is knocked back as ‘not a priority’, which is perhaps pronatalism at work again, unconsciously blaming those women without children (forgetting that there are similar numbers of childless men) for not having children, even though most people without children didn’t choose that, and even if they did, they did so for sound reasons and should not be ‘punished’ for it.

The line often touted by politicians is that ‘families must do more’, which is code for ‘women must do more’. But those ‘women’ who used to provide so much informal care in families and communities are most likely at work now, and families have been steadily shrinking, so even if you do have children, it may not be possible or practical for them to step in, should they be able to - they may predecease you, be incarcerated, have adult care needs of their own, live on the other side of the world or be estranged from their family.

But I didn’t have children so that they could take care of me!

If you are a parent, you may be thinking, ‘But I didn’t have my children so that they could take care of me!’ and this has often been said to my face when I raise this issue. My response is often, ‘Absolutely… when I was trying to conceive, it never entered my head either!’ which is met by a pleased nod. However, when I continue after a pause to say, ‘So, I’m wondering what plans you’re putting in place to make sure that doesn’t happen?’ the response is usually a hostile and shocked expression, followed by a swift exit from the conversation… Because you see, most parents do unconsciously rely on the idea that their children will be there for them (even if that turns out to be a bad idea), something that a psychological mechanism called ‘Terror Management Theory’ supports.9 And yes, it is indeed the case that some children aren’t there for their parents should they need support, even from afar by telephone, but it’s a very small percentage, with 94% of unpaid elderly care in the UK currently provided by family.10

The fact is, whether we have children or not, we all need to start having better conversations about later life and how we’ll care for ourselves, for each other, for family members and for those around us in our communities.

This will be the focus of my work and life over the next decade, and I already have some inspiring conversations, projects and resources to share with you on this topic. But most of all, I will be living this reality, and reporting my experience as I go. Because something I’ve learned over my years of community building with childless women is that when we come together, we are an awesome pool of resources, wisdom, kindness, empathy and dedication.

The way we ‘do’ ageing needs a revolution. A revolution of mutual tenderness, connection and support. And like all revolutions, it needs to start from the ground upwards, with each of us choosing to do this differently now rather than hoping that something or someone is going to fix this for us; we are the grown-ups now, we can’t dodge this one. And future generations of other people’s children will thank us for this - because changing the way we do ageing will benefit all of society.

Thank you for being one of my readers, I appreciate you very much! If you’d like to support my work you can do so by:

‘Hearting’ this post, so that others are encouraged to read it;

Leaving a comment (I do my best to respond to each of them);

Sharing this post by email or on social media using this link;

Taking out a paid subscription to this Substack in your local currency;

Leaving me a tip by buying me a coffee.

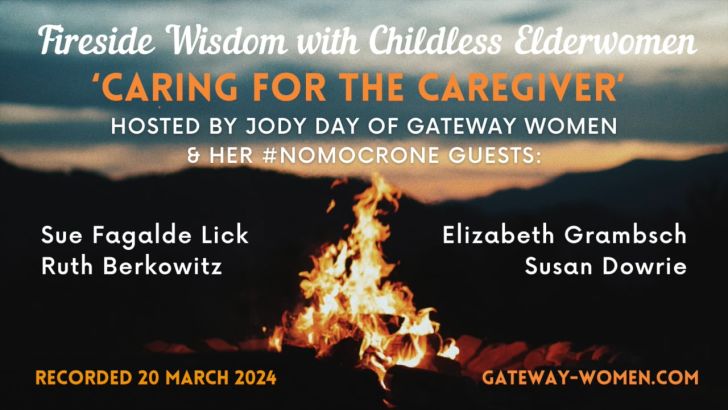

Watch: ‘Caring for the Caregiver’

On March 20th 2023 I hosted a conversation about all this called ‘Caring for the Caregiver’ with the powerful #NomoCrones (nomo=not-mother + crone is not an insult!) for our next Fireside Wisdom with Childless Elderwomen webinar. You can watch it, and find all resources mentioned here.

An excellent unpacking of how pronatalism oversells motherhood (yet under-supports mothers) can be found in Ruby Warrington’s Women Without Kids: The Revolutionary Rise of an Unsung Sisterhood (2023, Sounds True Books). The book includes material from her interview with me, which you can hear us discuss on episode 1: ‘Beyond the Non-Mom Binary’ of Ruby’s ‘Women without Kids’ podcast. Laura Carroll’s book The Baby Matrix (2012, Live True Books) was my chilling (and excellent) introduction to pronatalism, and I’ve often found that childfree-by-choice writers are more aware of the nuances of pronatalism that childless-not-by-choice women, or mothers, even though this is an issue that impacts all of us, whatever our gender and reproductive identity.

Orla Donath’s research in Regretting Motherhood: A Study (2017, Penguin Random House) sheds much-needed light on the taboo experience of women who regret motherhood.

Two new books on this topic exploring the lives of women without children are Laura Caroll’s A Special Sisterhood: 100 Fascinating Women From History Who Never Had Children (2023, Live True Books) and Nicole Louie’s forthcoming Others Like Me: The Lives of Women Without Children (2024, London: Dialogue Books). I have also been curating a gallery of almost 700 women (contemporary and historical) without children on Pinterest for many years.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. London: Penguin Modern Classics.

My essay ‘The Symbolic Annihilation of Childless Women in Films and Media’, written for World Childless Week 2023, goes into this in more depth.

This statistic is from the Ageing Well Without Children website and is repeated elsewhere, but I cannot find the source. If you know it, please can you share it with me/us in the comments?

This statistic is also from the Ageing Well Without Children website, and it did once mention its source, but it’s no longer listed. If you know where I can find it, can you please share it with me/us in the comments?

See Dr Mervyn Eastman’s excellent article for Independent Age, ‘Compassionate Ageism: Reinforcing ‘the terror of age; the weak, catastrophic victim of age’?’ Independent Age, 22 March 2019.

An excellent primer on Terror Management Theory is The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life (2015) by the researchers behind it, Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenberg, and Tom Pyszczynski. Review in The Guardian here.

My source for this statistic is no longer accessible online. If anyone reading this can point me towards another reference, I would be grateful!

Thanks for writing this. I’ve also been thinking about it a lot as it’s looking more unlikely that I’ll have kids (I’m 37). Two things keep standing out to me:

1. Intergenerational community and friendship is more important than ever. I’m excited to see how we tackle this challenge as more of us age and more of us are childfree

2. One I think about a lot right now is the blurry line between social life and family life: how they intersect, connect and are prioritised against one another when you don’t have kids. My thoughts are all a jumble on this but I know there’s something important to say here as I feel the tension constantly - I need to write about it so I can figure it out!

Oh, this really hits home: "The line often touted by politicians is that ‘families must do more’, which is code for ‘women must do more’. "

Many years ago, when my employer first offered long-term care insurance, I bought in. I am not in a situation where I have any likely family caregiver if I should need one, so it seemed like a good idea and was quite affordable then. But over the years, the premiums have been skyrocketing. It seems that the company was shocked by the amount of actual need, and vastly underestimated what they would have to pay out. I believe this underestimation was largely based on the fact that unpaid caregiving is so overlooked and undervalued by policymakers and business leaders; they didn't see it so didn't base their calculations on realistic expectations. They couldn't appreciate just how much time and energy and money was going into caregiving, not until those costs were translated into money that they, as a business, would have to spend.

The other thing that bothers me about policymakers who want family members to take on caregiving without government help, is that they are usually the same ones who resist requiring businesses to have paid family leave, overtime, and other family-friendly policies.