My mother didn’t have friends when I was growing up - partly because she lacked the skills after a brutal childhood, and having a violently controlling and jealous first husband didn’t improve things. It wasn’t until her sixties, when she and her later husband retired, that she gradually softened and began letting people in. At her funeral last year, I was moved to meet many who’d got close to her in those final years and, by their affectionate stories of her quirkiness, had really known her.

However, just as she wasn’t set up by her childhood with solid friendship skills, neither was I. By the time I entered young adulthood, I’d been let down or betrayed by all of my parental figures and, taking my cue from my mother, regarded relationships as transactional and disposable. I cherished my friends and boyfriends whilst they were around, but I had no illusions that they would stick around, or that they would miss me when I wasn’t. Having never been ‘missed’ by my own mother, and having never had trustworthiness modelled to me, I didn’t know what it was—but the kicker was that I didn’t know that I didn’t know that. I trusted too easily, not really understanding what I was doing, and I let people down too easily too, not appreciating that although I was used to being discarded, others weren’t. As the expression goes, ‘damaged people damage people’ and that was definitely my mother and, for a long time, me too. These days, having done the painful personal archaeology that is part of becoming a psychotherapist, I know it’s called ‘intergenerational trauma’ and I can choose not to repeat those patterns. But even so, friendship can still be a struggle for me, especially without the social glue of motherhood and grandmotherhood to bond over.

Many women first meet me through my public work as the founder of the childless advocacy and support organisation Gateway Women, and the version of me they meet, whom I call ‘Red Jacket Jody’, is energetic, amusing, empathic and pretty selfless. But she’s only a part of me—a genuine part, yes—but still only one of my personas. Away from the public eye, I’m both taller and quieter than people might expect, and I guard my time fiercely. I’m an INFJ on the Myers-Briggs scale these days, so I can easily be mistaken for an extrovert, but my social battery only really glows when I’m using my ‘meaning and purpose’ jetpack. The rest of the time, my favourite sound is silence and I’m often lost in deep thought, just as I was as a child—in fact, hearing stop daydreaming yelled at me is an easily recalled childhood memory. Adult me is energised by honest, vulnerable conversations and big compassionate ideas, but it’s rare to meet others with a similar appetite. Thank goodness for the internet, where like-minded souls can find each other, as here on Substack!

[Above] ‘Red Jacket Jody’ gives a TEDx talk, 2017

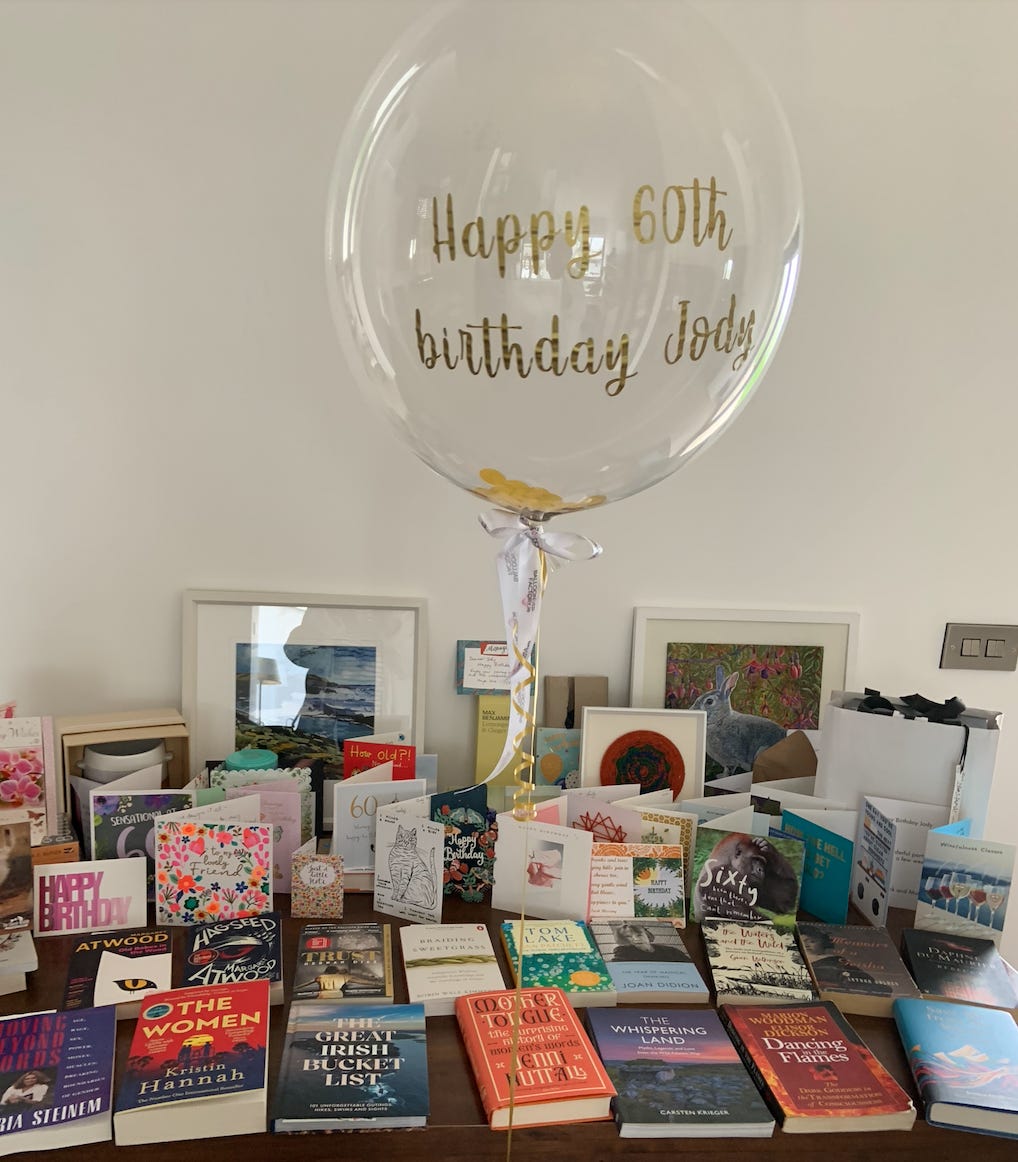

At my sixtieth birthday celebrations in July 2024, I chose to do most of the catering and organising because that way, I could dodge being the centre of attention by taking care of others; indeed, maybe unconsciously that was part of the appeal of motherhood? As a child, my birthday parties were pretty fraught affairs, if they happened at all and, as taking the focus away from my mother was never a safe plan, it’s still rare that I have a birthday celebration more than once a decade.

But this time, for my sixtieth birthday, and for the very first time, I had a wonderful time. Old friends (including the two pictured above) travelled from around the world and mingled with new local friends, neighbours and acquaintances from Ireland, and the weekend flowed with grace, good humour and love. At the end of it all, after the complete lack of drama or awkwardness, I had to face up to something that felt profoundly challenging to me: was this proof that I’d finally learned how to be a good enough friend? Was I really the genuinely likeable person that these good people seemed to think I was? (I also need to add that I’ve been sober since January, so there were no rose-wine-tinted glasses involved!)

To contextualise my surprise, let me wind the clock back a bit to my early forties, when I first hit the buffers of thwarted motherhood. I’d been on that track since my late twenties and, convinced that motherhood was a ‘when’ not an ‘if’, had kept up with all the ‘other’ couples in my then-husband’s and mine’s circle as they become parents; the way I saw it, their kids would be my kid’s friends one day. I followed their milestones on Facebook and sent Christmas cards and birthday cards, despite the diminishing returns on my investment. I watched them post photos of parties and joint holidays that I only learned about in retrospect. It was painful, but I was doing this for my kids. Except I didn’t have any.

And then once I didn’t have a husband either, I might as well have slid off the map into ‘here be dragons’ territory. I became the bad fairy at the christening, pushed out of mind and off the invite list.

In 2012 I gave an interview (which went viral) to The Guardian where I talked about my experience of childlessness and how it was impacting my friendships. Naively, I thought it might help my friends understand and empathise with my experience, but as I didn’t yet understand the pronatalist-driven status quo supporting their behaviour, the article instead sealed my exclusion from the group. I used to joke that as a single, childless, middle-aged woman I was ‘social plankton’, the bottom of the social food chain, and that the only invites I got were to dental checkups. But this self-deprecating humour belonged to ‘Red Jacket Jody’; in my private life, I was often excruciatingly lonely and wondered why friendship seemed to be such a challenge for me.

Issues with female friendships (particularly with those who become mothers when we do not) are such a common part of the involuntarily childless experience that I later termed it ‘the friendship apocalypse’ of childlessness.

And although I wouldn’t wish this painful experience on anyone else, it did come as a huge relief to me to discover that it’s something many childless women can identify with; truly, I just thought I must be a rubbish friend!

Many childless women have felt anticipatory grief when yet another close female friend announces their ‘happy news’, and even though they often reassure us that ‘nothing will change’, we know that it will and that it has to; modern motherhood can be an overwhelming, all-consuming and surprisingly private affair. And although around 1 in 5 women are reaching midlife without children, and both voluntary and involuntary childlessness are on the rise, it’s still seen as a deviant identity for women under patriarchy (er, JD Vance anyone?) So much so that many women without children are actively or passively shunned by mothers, even by family members, when they try to form relationships with their kids. Sometimes it seems that the ‘village’ it takes to raise a child can feel more like a gated community.

The friendship issues that can get stirred up when we long to be mothers but have to watch from the sidelines can be treacherous to navigate. So much so that in my book Living the Life Unexpected I referred to it as ‘the baby elephant in the room’ - the thing that we don’t know how to talk about.

Female friendships are built on shared intimacy and vulnerability, of revealing the most private truths of our lives, but when motherhood/non-motherhood stirs up envy, that’s something we don’t know how to talk about.

New mothers may be mourning the loss of their pre-motherhood identity, and envy their childless friends their freedom, imagining that their friends’ lives resemble what theirs were like before parenthood (when in fact the ‘freedom’ of involuntary childlessness may at times feel intensely lonely and, for a while, saturated with grief); childless friends may find the grief and envy of witnessing their dear friend’s arrival at the promised motherland excruciating, yet find it impossible to articulate that without sounding bitter or unsupportive. (I recognise that the dynamic can be very different if you are childfree by choice).

Envy is one of those emotions nice girls aren’t meant to experience, and it’s both painful to feel it, and to feel it hit you, because it leaves no room for nuance.

But if we can’t talk about it, envy can lead to a slow withdrawal of intimacy from the friendship until it becomes a parody of its former self, or ghosts into memory. I recognise now that I lost a few friendships to unprocessed envy when I got married at twenty-six, and again when I met my new life partner in my early fifties after spending my midlife single.

Whilst childless women can feel hurt that their mother friends are unable to make time for them anymore one-on-one; mothers may feel hurt that their childless friends don’t understand that unless they’re prepared to fit around their fast-changing schedules or muck in with family life, it’s just not possible to see them. Yet one of the tough experiences that many of us who are childless share, particularly if (as in my case) everyone you knew who wanted to become a parent, did so, is that although mothers’ lives have expanded to include more people, ours have mostly likely contracted. I know that some of my mother-friends who survived the #FriendshipApocalypse years thought that my life at the time was full of parties, travelling and socialising, whilst theirs were ones of being stuck home with the kids. Yet who did they imagine I had left to socialise with? Children often bring a whole new tribe of people into your life; childlessness not so much so. And why, as a woman in my forties and fifties, did they imagine I’d still be doing the sort of things we’d done together in our twenties?

Over time, having metabolised my grief and rediscovered my innate sense of worthiness, any envy I might once have felt for those who had become mothers dissolved and I found it easier to hear their difficulties and empathise with their struggles without judgement. However, it still saddens me how little imaginative empathy is directed towards the challenges of living life as a woman without children (by choice or chance), and often without a partner too, whether it be the existential dark night of the soul many of us pass through as we grieve the loss of the family we longed for, or the lifelong challenge of living outside the only acceptable pronatalist identities for women, those of ‘partner’, ‘wife’, ‘mother’ and perhaps one day, ‘grandmother’.

None of my friends has yet become a grandmother but here in rural Ireland, most of my neighbours are a little older than me, and all of them have grandchildren that they cherish. Understandably, much of their spare time is spent hosting them, travelling to see them, or helping to care for them. But luckily, we can connect about other things, and they’ve shown a genuine interest in me and made me feel very welcome. I recall a sunny Sunday afternoon in a pub garden when the female chat was all about grandchildren and I was fine with it, even though I had nothing to contribute other than to ask questions and to bask in their joy; I did so with a glad heart because they have been inclusive to me in other ways.

However, I also recall the time a couple of years back when I was buttonholed at a social event by a usually quite fascinating man who waxed lyrical about his grandchildren, and about the unique love that’s only possible between grandparents and grandchildren, for a full hour, even after I tried to change the subject several times. Not only was there a limit to the number of times I could genuinely say, ‘How lovely for you,’ it also began to grate that my experience as someone who’s ageing without children, let alone grandchildren (which I discreetly reminded him about) wasn’t given even a moment’s consideration. It reminded me of how falling in love can turn the object of your love into a demigod and how, if you could get away with it, you’d talk about nothing else. But as adults, we know that such behaviour is immature, and we don’t indulge it.

Sometimes, part of the experience of childless/mother friendships can be that as their children grow up and together we pass through the menopause transition, things may begin to change again: sometimes we get our friends back for a while only to watch them once more submerge their identities into doting grandparenthood; other times they can adore their grandchildren and want to invest in a wider range of friendships than simply those that share the grandmothering experience. And just as it seemed that we couldn’t have predicted what ‘kind’ of mothers our friends would become, it seems the same holds true for grandmotherhood…

Female friendships have been the site of some of my greatest joys and biggest heartbreaks.

They hold a mirror to my anxieties about my likeability and offer the opportunity for riotously healing belly laughs and the bone-deep comfort of being fully known. As my colleague, the writer and therapist Stella Duffy says, ‘Post-menopausally, we’re all infertile’. Maybe now, as I unravel into my croning, the dark honesty of this time of life might just be the compost friendship needs to thrive? I do hope so.

Thank you for being one of my readers, I appreciate you very much! If you’d like to support my work you can do so by:

‘Hearting’ this post, so that others are encouraged to read it;

Leaving a comment (I do my best to respond to each of them);

Sharing this post by email or on social media using this link;

Taking out a paid subscription to this Substack in your local currency;

Leaving me a tip by buying me a coffee.

As I read the essay I tried to stay on the surface, not wanting to get deep at the moment . . . and yet, that last sentence snagged me and I sit with tears. The sentence about "I sure hope they want to", be friends now. I didn't know I had so much feeling still active around all this. The opening of the world of friendships when one becomes a parent, and the opposite if that never comes. And now, turning 60 later this month, the longing still burns. For a child yes, but deeper and bigger too. For a full table, for a place of belonging, to be seen. Thank you Jody for again giving words to living this life. From the bottom of my heart thank you.

This spoke so deeply to me and shone a light on an area that I have just historically considered myself bad at, but your insight allowed me to look at it from a different angle. Thank you for so often giving words to feelings I don’t yet have the ability to articulate, it is beyond appreciated