As I travel through the last month of my fifties, and with many years of childlessness behind me and grandchildlessness ahead of me, I wonder, have I learned enough about how to have hard conversations?

You know the ones…

The ones with your sister (the family madonna with the grandkids) who, yet again, gets to decide who, what, where and how a family event takes place, or whose voice seems to carry a dispropriate amount of weight in heavy conversations about family traditions, possessions, holidays, wills and inheritances.

» Do you think we’ve been living under a rock all these years?

The conversations with old friends, those that you really thought had understood that you’re the wrong audience to monologue with about their kids, yet who start doing it all over again, but with brass knobs on, about their grandchildren.

» We get it; they’re adorable but we got that after the first fifty photos…

The ones at work when, as an older woman, your expertise and knowledge are relied upon by the whole team, except when it’s time for promotion or participating in a zeitgeisty new project.

» Erm, hello? We invented the internet?!

The conversations with your parents and siblings who expect that you, as the daughter without children (and maybe without a partner too) are the default carer for your ageing parents, and are expected to do so without complaint, or any meaningful logistical or financial support from your siblings…

» So if I take this financial hit now, you guys are stepping up to the plate to care for me when I might need it, right?

The ones with the old white guys with brass plaques on their doors, who’ve decided that they know best about your career, finances, uterus, planning application, legal issues, etc, and seem to go deaf when you start speaking up, especially now you’re no longer on their fuckable list.

» Jeez, you were never on mine; still aren’t.

I grew up in a home where disagreements were settled with a lot of shouting and often violence and, as a result, my nervous system is fairly conflict-averse. And even if your upbringing wasn’t like that, it still seems rare that girls get adequate role-modelling and support around speaking up for their needs, correcting misunderstandings and seeking to redress injustices… More often, we’re patriarchialised to ‘keep the peace' and 'not rock the boat'.

If I look back at my adolescence, perhaps it’s not surprising that against a chaotic background of alcoholic and relational dysfunction, I chose to leave home whilst still a teenager (although I continued with my A’ levels at school). I was an angry young woman but I didn’t understand why. It was the eighties and I got involved with my local branch of CND (the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament) and found that directing some of that energy into a ‘cause’ helped. But only slightly.

At seventeen I was blossoming from a lanky and awkward-looking duckling into a beautiful swan and from the way men now reacted to me, I realised that although I’d been powerless against men as a child, there was a new dynamic at work now; I had something they wanted.

By the time I’d left my small hometown and moved alone to London at nineteen, I’d understood that the way I looked was powerful; that it had currency. Unfortunately, as the unmothered daughter of an unmothered daughter, and moreover with one who was too jealous of the potency of my emerging womanhood to help me understand the risks that came with it, I arrived in the big city like a heat-seeking missile. I’d seen how easily my mother’s physical, psychic and financial freedom had been controlled by men, and I had no intention of allowing the same to happen to me.

My first serious relationships were with men who frankly adored me, and put up with every kind of bullshit just to be with me. And the more accommodating they were, the kinder they were, the sweeter they were to me, the less I respected them. I was an unfeeling rock they threw themselves pointlessly against. With the benefit of maturity and therapy, I look back on that traumatised young woman with such tenderness; I was like a feral kitten, desperate for nourishment but who’d scratch anyone who tried to get close, so I never knew what it was to be fed, to feel safe. I ‘knew’ that all they wanted was my body and that everything else they offered was just a lie (to themselves too.) I took my anger out on them and, looking back, I’m so sad for the hearts I broke in the process.

And then I met the man who would become my first husband. I was twenty-two and he was seven years older and from a privileged, English upper-class background. The whole Hugh Grant floppy hair and cut-glass accent package. He treated me like an exotic pet, despite being someone who shouldn’t have been trusted with a houseplant. So of course, I fell hard for this one. But we fought as hard as we loved. I was a self-taught, ambitious left-wing kid from the wrong side of the tracks; he was a privileged, entitled entrepreneur, and found my passion for championing of the rights of the underdog amusing and naive. Many were the times when I’d storm out of restaurants (having been to very few in my life before I met him) ablaze with fury, yelling that I wanted nothing more to do with him. But yet I couldn’t stay away. A song from childhood, Roxy Music’s ‘Love is the Drug’ made sense to me for the first time.

If you’re wondering why I’m telling you all this it’s this: one day, deep down in my unconscious, I made a deal with my true self. I said to it: ‘If I stop doing and saying the things that create the problems between us, this relationship will work.’

And it did. I put the genie back into the bottle, and I did so willingly, without even enquiring what the cost of that might be. I stopped spending time with my ‘old’ friends, the ones I’d made at school and from my first few years in London, and whom he belittled; I stopped fighting against his Pygmalion tendencies and allowed my accent, vocabulary and social graces to be polished to suit him; and although I never stopped being left-wing at heart, I stopped being an active political animal at all. I even stopped being a feminist. I decided that I’d rather be loved.

Reader, I surrendered. Reader, he adored it. Reader, I married him.

He never asked me to do it, but I gave away my power so that I could be his wife. My mother told me not to marry him, but I ignored her. Take advice from a woman on her third marriage? I don’t think so. Ha! Turned out she knew what I was doing, even if I didn’t. Nor did he. My disguise was so good, I didn’t even know I was wearing one.

Until one day, after many years of being in a relationship where his needs were the only ones that mattered (something I wholeheartedly colluded in; the daughters of alcoholics make excellent codependents), the genie exploded out of the bottle. With a Kaliesque outpouring of pure white rage that flowed out of the top of my head at a million miles an hour, I blew apart the psychic contract I’d made with myself. (I later found out that I experienced something called a ‘Spontaneous Kundalini Awakening’.)

I woke up in my life, looked around me, and was appalled.

I was thirty-seven and we were just about to start fertility treatments for my ‘unexplained infertility’. But my ‘self’ (in the Jungian sense) simply wasn’t having it. The voice that had been suppressed all my life, first by others, and then by myself in the service of others, erupted into my consciousness with a fierceness that burnt away everything. In the aftermath, I found myself divorced, single, middle-aged, broke, broken, friendless and childless - but finally free to speak my truth.

It cost me everything; the genie had collected.

So back to today, and here I am, here we are, menopausal and post-menopausal women with a lot of experience and a lot to say for ourselves, but as well as perhaps lacking the skills to do so, we live in a culture that calls us ‘harpies’, ‘bitter’, ‘hags’, ‘witches’, ‘harridans’ or [insert derogatory term here] when we do speak truth to power. (And for those of us who didn’t have kids, we don’t even get to play the ‘As a Mother card', so we’ve got zero skin in the game, apparently.) Shame: the most potent tool of social control; nothing shuts a person down faster.

But perhaps one of the potential benefits of the IDGAF (I-don’t-give-a-f**k) energy of post-menopause might be that we’re simply no longer interested in keeping the peace?

So, how do we find the courage and where do we learn the skills to use our voices as older women wisely and effectively?

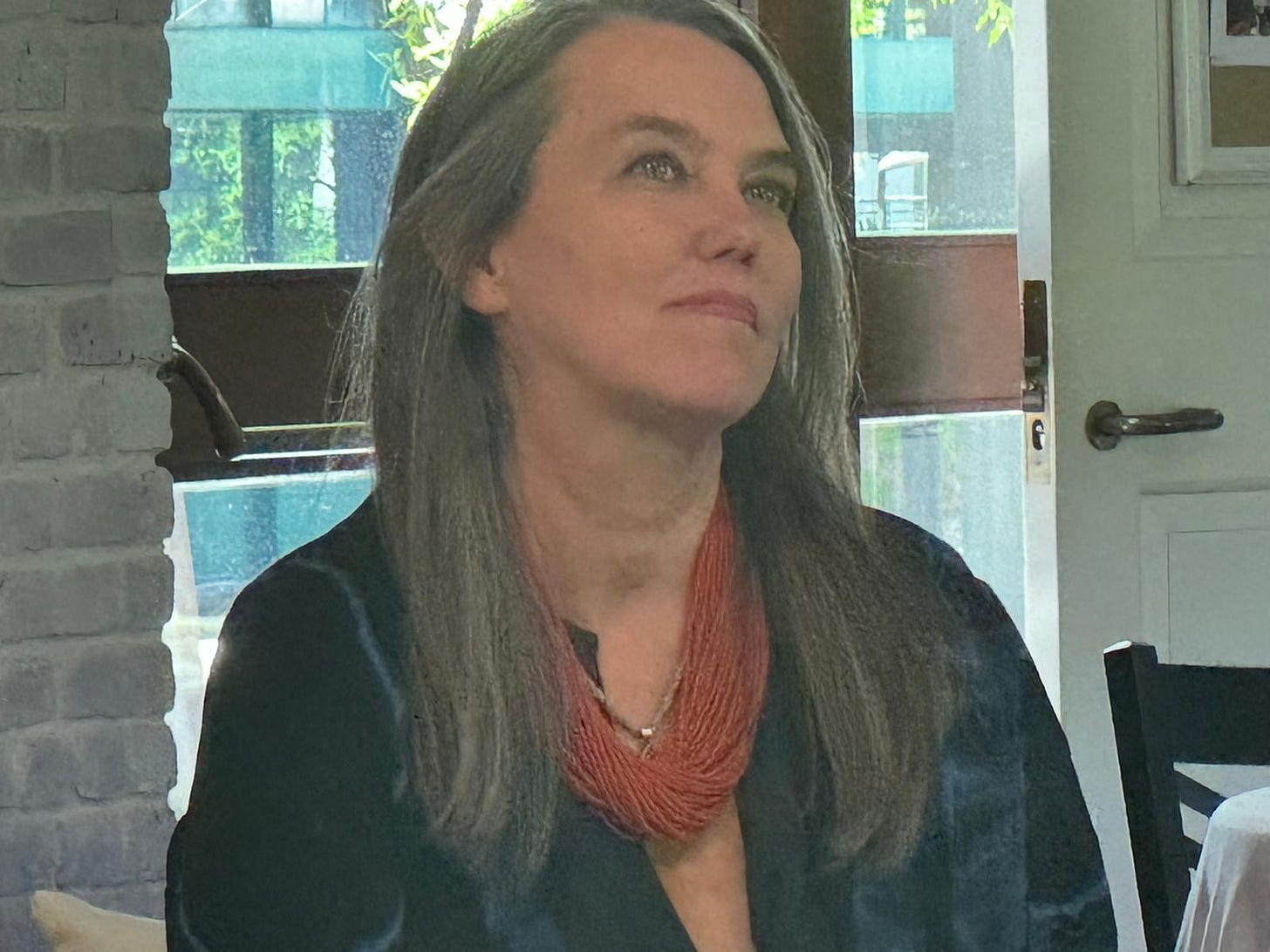

For me, the first work has been (and continues to be) internal. Much as I had to radically wrestle my self-esteem back from the pronatalist constructs that branded me as a ‘failed female project’ for being childless and divorced at midlife (and which I wrote about in my book Living the Life Unexpected1) so it’s been with jumping the shark from midlife to young elderhood. These days, my hair is mostly silver and my waist is a distant memory but I’ve reclaimed the word ‘crone’ for myself, (I’m on Instagram as @ApprenticeCrone).

Etymologically, crone hasn’t always been an insult; its deep origin is thought to come from ‘Rhea Kronia’, (Mother of Time) and is connected to black creatures, such as the crow, which is sacred and related to death.2 I’ve written before about how the crows have been speaking to me this last half-decade, and the hooded crows native to Ireland (called Cág in Irish) have an additional hangman’s vibe about them too.

Other feminist writers are doing something similar to reclaim language too, such as Sharon Blackie’s book Hagitude3 (which I’m interviewed in) and Victoria Smith’s Hags: the demonisation of middle-aged women4 (which I’m referenced in). And as those of us born in the sixties continue to move through our sixties, I think we can expect to see more of this kind of thing; we’re a mouthy and practical cohort who are used to sorting shit out for ourselves. I very much doubt we’re going quietly into old age. Nope.

And then the second part of this is learning the skills and acquiring the confidence to speak up and speak out. (Like the boys around me were taught and praised for doing.) Certainly, during my years of fielding all manner of intrusive, judgemental and inappropriate questions about my ‘lack’ of children, or my relevance as a human being because of this, I’ve developed some form in this area, but I still have a lot to learn.

Because if as elders, we can’t find a way to model this for younger women, how will anything ever change for the better?

Thank you for being one of my readers, I appreciate you very much! If you’d like to support my work you can do so by:

‘Hearting’ this post, so that others are encouraged to read it;

Leaving a comment (I do my best to respond to each of them);

Sharing this post by email or on social media using this link;

Taking out a paid subscription to this Substack in your local currency;

Leaving me a tip by buying me a coffee.

Day, J. (2020). Living the Life Unexpected: How to Find Hope, Meaning and a Fulfilling Future Without Children. 2nd Edition. London: Bluebird/PanMacmillan. Free sample chapter at https://gateway-women.com/book

Walker, B. G. (1996). The women’s encyclopedia of myths and secrets. Edison, New Jersey: Castle Books. Quoted in: Ott, J. S. (2011) ‘The Crone Archetype: Women Reclaim Their Authentic Self by Resonating with Crone Images’. Retrieved from Sophia, the St. Catherine University repository website: https://sophia.stkate.edu/ma_hhs/17

Blackie, S. (2022) Hagitude: Reimagining the second half of life. UK: September Publishing. https://hagitude.org/the-book/

Smith, V. (2023). Hags: the demonisation of middle-aged women. UK: Fleet; Little Brown Book Group. https://www.littlebrown.co.uk/titles/victoria-smith/hags/9780349726984/

I’ve never felt the sting of childlessness or being single most of my life. Oh I’ve had partners and even a few husbands along the way but my best years, especially the last twenty-five, have been unencumbered by the responsibilities imbedded in intimate relationships and the raising offspring. Looking back I know I would have never had the interesting life I’ve lived had I taken a more traditional path. I too have a sister with a husband and children and grandchildren who’s “in charge” of family holidays and traditions but she is also the sister who took responsibility for our mother despite having a demanding career and raising a family while I galavanted around the country. I don’t resent her. I admire her. I love her. And I’m grateful that she’s “in charge” keeping our family traditions alive and bringing us together. I think if we are comfortable in our skin, live the life we’ve chosen and accept that there are trade offs for our independence, the voices of the critics become dimmer and our own stronger. You are correct, the middle years are the most challenging, but at 75 I can attest that remaining true to oneself leads to a greater sense of peace and satisfaction. Play the long game.

So much to process in this post -- thank you, Jody, for sparking thoughts that I'll be mulling for a while.

Yes to the idea of having and modeling courageous conversations! Why are we here if we're just going to acquiesce or stay silent?

As I age, I find I focus less on biting my tongue and more on sharing my perspective in ways that preserve my relationships.

A month ago, I visited my local post office for the third or fourth time about the same delivery issue (argh). As I stood in line, the guy behind the counter recognized me, and I could read the "uh-oh" in his eyes.

At the end of our conversation, he said something that I took as a sign of success: "You are our nicest complainer."

And it does seem that the issue has been resolved (knock on wood!).