A version of this was first published on my Gateway Women blog in 2016 when I was a month shy of 52; I’ll be 60 next month. I had been single for several years when I wrote it; I have been partnered again since I was 52. My thinking has evolved in the last 8 years, but the questions I started asking in this piece have been good ones…

I don't really know how to start this, as there are so many taboos and niceties banging against my consciousness, both as a woman and a feminist. But here it is:

I'm nearly 52 and men don't notice me any more and it turns out that I mind that quite a lot.

This new awareness was brought home to me whilst on a two-week holiday in Southern Italy. I was staying with friends for the first week; young middle-aged parents with their small children and, fully released from the grief of childlessness, I found myself able to open my heart to their children without any sadness surfacing; I had long hoped that one day being around children wouldn't be so painful, I hadn’t dared hope it could this joyful too. The second week I spent alone (as planned) to write, and it too was full of unexpected feeling, this time a new grief: the grief of ageing.

I'd met the father-friend during the life-changing year I’d spent as an au-pair in Rome in my early twenties. During that time, my exposure to the dramatic flair with which Roman women performed their femininity like a weapon helped guide this gawky English girl into a more confident young womanhood. In Rome there was a collective sense of admiration for women that was alien to my Anglo-Saxon upbringing, and living around it woke something up in me. I returned to London feeling that I'd got the best of both worlds: an English sensibility and feminist mindset, topped with a froth of Italian bravura and polish. Subsequent visits to Italy over the years had always reminded me of this, and I've loved the way that Italian men were able to show me, by their courteous behaviour and admiring glances, that they appreciated my presence; my experience of British men was quite different in that they either seemed to stare at you guiltily (or creepily), flirt with you when they were pissed, or yell coarse and intimidating comments at you from building sites. Not good.

And although I've been circumstantially and peacefully celibate for several years now, I did have it in my mind that perhaps I might, should the opportunity present itself, have a little dalliance with the opposite sex in Italy... It wasn't a fully formed thought, more of a 'let's see', and I carried the idea lightly, as I’ve grown to relish and cherish my single life after many years of drama-filled partnership from fifteen to forty-five. I had an image in my mind of one of those soft-focus summer movies where middle-aged women find romance, even love, in Italy. But life isn't a Hollywood film and the reality was that I discovered, to my shock, that I’ve become completely invisible to Italian men; I’ve become 'Signora'. And if I’ve become invisible to Italian men, then surely I must now be invisible to men generally… I used to joke that all a woman had to do in Italy to get male attention was to wake up and have a pulse — I was wrong — she needed to be in her child-bearing years (even her infertile child-bearing years, as I'd been.)

Since that holiday, I’ve tried to discuss this realisation with a couple of people and, apart from some of the more reflective souls, most have seen it as me fishing for compliments about my looks. 'No, that's not true!' they've exclaimed, in mock horror or, 'Don't be ridiculous, you're still a lovely looking woman!' and, of course, 'But look at Helen Mirren... it's perfectly possible for an older woman to be foxy...' (The fact that I've never aspired to being 'foxy' as long as they've known me is suddenly irrelevant.)

Even when I've clarified that my looks weren't what I was talking about, but rather my feelings of sadness as I come to terms with this part of my identity as a woman ebbing away, this loss of something ineffable which I've taken for granted, this mourning as I shed the skin of youth and enter the new, and not-yet-known territory of my 'young elderhood', it's as if they can't hear me.

I’d mention the (very normal) menopausal weight gain around my middle which so effectively unconsciously signals my post-fertility and they’d look horrified, their eyes darting around to see if anyone else had heard. 'Are you depressed? they’d say or, 'Have you tried internet dating?' The fact that I wasn’t talking about wanting to be in a relationship, but about how differently I’m seen by society, and by men in particular, got lost in translation.

The tone of these conversations felt so familiar to me and then I realised why - it's was like trying to talk about childlessness all over again.

One of the main reasons I started writing my blog Gateway Women in 2011 was because when I’d try to talk about the pain, grief, isolation and devastation of my childlessness to friends or even therapists, they’d say the same sort of things back to me: 'Oh, don't worry, you'll meet someone!' or, 'But you look so young for your age, you've got loads of time!' or, once again, bring up bloody Helen Mirren. After a while, I stopped bothering trying to explain the complexities of coming to terms with my childlessness, because nobody could hear that I wasn't asking for reasons not to give up hope of motherhood—I was talking about what it felt like after you'd given up hope. But it was like shouting into the wind, so I stopped, and wrote a book instead.

By attempting to talk about the feelings of loss that ageing has stirred in me, once again, I'm trying to have a conversation which is not socially acceptable, a social taboo even, because it involves irrevocable loss, the spectre of loneliness, the decline that leads to death. All the stuff we don't want to think about or talk about, thank you very much.

Many of my peers are dealing with very ill and dying parents, and one of them is in a coma, not expected to survive. My darling cat is getting on in years too, and often when I return home to find her asleep, I gently call her name and feel a flood of relief as her consciousness flickers to life. I've taken up gardening with a passion and perhaps now understand why so many older women seem to love it; it's good to be able to make something grow when so much around us is reminding us of death.

I've noticed that the media discourse around ageing women seems to fall into two camps: either it's a disaster (which we could have avoided if we'd been more prudent, luck/privilege has nothing to do with it apparently), or it's a carefree time of adventure (cue skydiving pensioners).

However, whichever ‘camp’ others decide you belong to, disaster or adventure, it does seem to be mostly about how you look. I’d been collecting inspirational images of older women on a Pinterest board for a while, but I gradually began to notice that they were surprisingly homogenous: pleasing-looking white women with lustrous heads of long silver hair sitting atop very slim bodies. Hmmm. So I stopped pinning those and instead felt drawn to the individualism of the Advanced Style brigade, but then they too began to bother me with their ubiquitous 'When I am Old I Shall Wear Purpleness' eccentricity (inspired by Jenny Joseph's poem), and that isn't me either. Yes, I was a wild dresser in my teens and twenties when I lived, worked and breathed fashion, but since my mid-life divorce, I’ve returned to the more androgynous style of my youth. Why should I have to be flamboyant as an older woman just to claim the right to take up space?

I was a bookish child and quite a serious young woman. From around the age of fifteen until midlife, I’ve lived in a body which, by the whims of culture, has been considered 'attractive'. I never claimed any credit for this accident of genes and, having never been admired or praised as a child for my looks (or anything else), I found the attention bemusing and never took it seriously, as is often the case with privilege. Around the age of forty-four, when my last-chance-to-have-a-baby relationship ended, I was so relieved to be free of the drama of it, that being single came as a relief. And from that inauspicious start, I've discovered, to my delight, that the solo state suits me very well, much more so than I expected. Yet deep down, I've been holding on to an idea that if I wanted to be in a sexual/romantic relationship again, I could find one without too much difficulty (finding a good one, maybe not so easy!)

What I hadn't realised until Italy is that during those years from 45 to 51, as my hormones shifted from perimenopause to post-menopause, so too had my pheromonal signals to the opposite sex; I'm shocked how much I minded although I'm getting used to it. Writing this is part of getting used to it. It feels like I'm 'coming out' again, just like I did with childlessness. I feel vulnerable, worried about what you’ll think: 'How can she be so vain, so self-obsessed?', 'Why is she worried about something so banal as her looks?' David Hockney once said 'Your face belongs to other people' but I don't want them to have that power. I resent it even though I now appreciate that my ‘pretty privilege’ opened so many doors for me in my life.

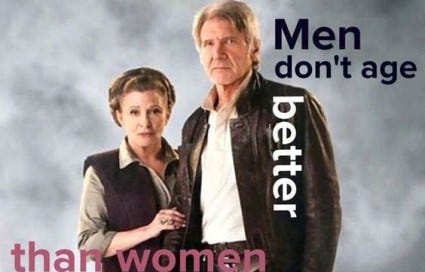

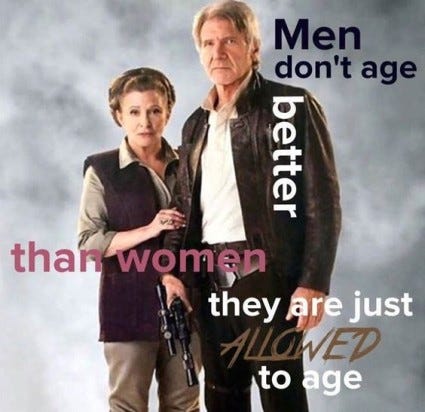

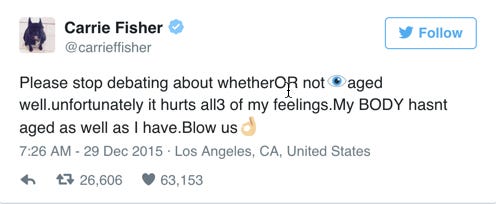

I'm with the late Carrie Fisher who, whilst acknowledging that her youthful figure had been key to her role as 'Princess Leia' in the original 1977 Star Wars, pushed back on Twitter against those who vilified her for having the temerity to appear on screen in the 2015 sequel as a older woman:

And it's not all about sex, or the 'male gaze' either. It's about being treated with respect as an ageing woman in a society which accords us very little space, and even then only if it involves being (or having once been) heterosexually partnered and fertile as wives, mothers and grandmothers. The only socially acceptable roles for older women without children are aunt or godmother, but once again, they involve a connection to the nuclear family unit. Without that, things very quickly slide off into caricature and cruelty— the crazy cat lady, the witch, the dried-up hag, the harridan, the career woman, the sexless spinster. If a woman's only currency within patriarchy is her youth/fertility (and then only when it’s in service to the 'male line', hence the status quo hysteria around gender identities), once this window has closed, and unless a woman is somehow involved with care of the male line, she's redundant. Hence the invisibility. It's brutal and it's basic and we can dress it up in as much empowering language as we want, but it’s a gristly nugget of internalised patriarchal conditioning to be digested, metabolised and transformed.

We cannot change what we will not talk about.

There was a moment in Italy that summed it up for me. I was in a restaurant having dinner alone and quite at peace with that. I'd finished eating and wanted to get my bill, but when I tried to get the waiter's attention, I couldn't. I looked to my left and saw that at the reception desk just a few metres away, a woman in her late twenties was having a mildly animated conversation with the head waiter, and 'my' waiter was gravitating towards that. I noticed, almost anthropologically, that there was a mating ritual of some kind in progress, and understood that until this had been concluded, neither of the young male waiters would notice my signals for the bill. I saw it as a biological fact and felt no rancour. And then the young woman left, and I signalled for my bill again and they immediately saw me. She was still potentially fertile; I was not, and biology won. Yes, I have other qualities; no, I do not define my value purely on biological terms. But in that moment it was all about biology, about hormones, about pheromones. It was as if the young men came out of a trance after she'd left and remembered where they were and what they did for a living. She was not an exceptionally beautiful young woman, and the exchange was not, to the casual observer, a highly charged flirtation. It was something much deeper, much less conscious...

All change, even good, hoped-for change, involves loss. And whilst I'm looking forward to my elderhood and already enjoying the renewed mental clarity and emotional stability that being post-menopausal offers, letting go of my youthful self is bringing up a lot of grief; I know grief, I respect grief and I trust that this loving energy that has got me through so much change before will get me through this one too, and that on the other side is a reality that I can't yet know, because I'm not that person yet.

I don't need an 'anti-ageing cream' because I'm no more anti-age than I was anti-youth. Each stage has its time and its power. But now I understand why my mother's generation called the menopause 'the change'; because it comes with a powerful side-order of loss.

Ageing doesn't have to be of the ‘disaster’ variety, and somehow I'm sure that most of us who are the skydiving types will have done so already (and might do so again), but surely there must be quite a bit of wiggle room in between them? And it's into that in-between space I’m aiming as I do my best to transition mindfully into my 'young elderhood'. And no doubt once that's complete, and I've shed the skin of youth and have embodied what comes after, it'll be time to shed that skin too and move into the next stage. Ageing is not an event, it’s a lifelong process.

And hopefully by then, I’ll have worked out what to wear. I just know it won't be purple. It's never suited me.

Thank you for being one of my readers, I appreciate you very much! If you’d like to support my work you can do so by:

‘Hearting’ this post, so that others are encouraged to read it;

Leaving a comment (I do my best to respond to each of them);

Sharing this post by email or on social media;

Taking out a paid subscription to this Substack';

Leaving me a tip by buying me a coffee.

I’m a 53 year old single never married childless woman who has had a similar experience of my body being attractive to men - from too young an age - and having that be a defining characteristic of my life for decades, then not.

I take comfort in knowing how much the hormones are the driving force. Just as my entire perspective has changed since the change of life shut off my attraction to men and my tolerance for their toxicity, I fully grasp that my dead womb and the external evidence of that is why most men no longer see me.

I was almost embarrassed when the change of life revealed to me how much my thinking had been shaped by hormones and the biological imperative - I can hardly blame men for having the same experience of life. If anything I feel sorry for men because I think those drives continue to make many of them stupid their entire lives, while many women seem to have a renewal in postmenopausal life when they become free of male gaze and their own drive which compels people pleasing.

There is no avoiding this time of life, we are lucky to have gotten this far. Embrace and enjoy it!

I’m having a very different experience. I’ve always been overweight. I came out of the womb a chubby baby with a head full of black curls and at 61 I’m not much different. And because I’ve been bigger than most I’ve been ignored by men because of my looks for most of my life. Or I’ve gotten the creepy gross attention especially in my teens. But I didn’t go to prom. I didn’t have a boyfriend etc. I was always the friend and not the girlfriend. I wasn’t ugly - but I was the great personality girl. I did eventually marry at 40 but to a man who doesn’t notice or care what I wear or what I look like (he met me when I was at my fittest). The thing is at my age I feel so much relief. Maybe if I’d been pretty and thin I’d be missing the attention but I don’t. I care what I look like. But it’s totally for me. I like stylish clothes (my young nieces give me the thumbs up) but I dress for me. I now feel totally myself and that’s the best feeling.